|

In This Issue...

- Live and Let Die

- In the Field with Dr. Stan B. Floresco

- Dr. Jaak Panksepp - A mind of joy and research

- IBNS 2017 in Hiroshima, Japan

- Hobby Much?

- Trending Science

- Member News

Live and Let Die

by Molly Kent

I was about two weeks from depositing my thesis dissertation for my PhD in Neuroscience, when I got a call that I had never expected. I had recently gone in for some medical tests about some mildly annoying symptoms that I thought were probably hormonally driven. Just to make sure that we knew what was going on, the physician ordered a CT scan of my brain. , It was possible that I had a pituitary tumor since my sister was diagnosed with one a few years earlier. The thought of a pituitary tumor was that was the worst- case scenario. Back to that life-changing call. The day of the CT scan, I received a call while driving home after finishing lab work for the day. As the doctor began to discuss my scan, he stated that he felt I needed to go straight to the emergency room. As a scientist, let alone a neuroscientist, I wanted to know what was going on. The only information I was given was that there was an anomaly on my CT scan that was not indicative of a pituitary tumor and I needed more tests. Needless to say, that call got my attention!

Once at the ER, after having a MRI scan, I was admitted me to the hospital for the night until there was more information about my diagnosis. For me, the most frustrating part was I couldn't get information about what I had spent over the past decade of my life studying—the brain---MY brain! I needed information to start processing this new information.

The Neurologist, who I knew from my neuroscience program, provided a small oasis of familiarity in this strange new world I had reluctantly entered. As we both evaluated my MRI scans, I saw the bright spot on the scan. I was sent for more tests…was I having a stroke? …did I have an infection? The neurologist confirmed that it didn’t look like either of those possible diagnoses. At that point the most logical diagnosis was difficult to ignore. My next statement was, “okay-- so barring any other crazy options, I have a brain tumor.” My scientific thought strategies were able to regulate the emotions that were shifting somewhere in my brain that was all of a sudden being so closely scrutinized. I was told that, indeed it was most likely a tumor, but further tests were necessary. After the tests were evaluated, the radiologist stated I likely had a glioma, 3.7cm x 2.5cm x 3.5cm in size in my right temporal lobe. The size was somewhat alarming to me a 4 cm tumor in my brain seemed really big. Perhaps I should preface with the fact that my dissertation focused on a stickleback fish brain that was approximately 4mm in size. To provide an accurate model of the tumor, I used a silly putty substance that had been sitting on my desk as a stress reliever for years, and measured out the sizes using my handy ruler. The shape resembled a small to medium chicken egg.

Once home from the hospital, I tried to focus on another stressor in my life---finishing my dissertation. There were edits to complete before sending the most recent version to my thesis to the committee to get approval for it to be officially finalized. Although the tumor had just rocked my world, I had spent too much time in graduate school to let anything keep me from placing those letters behind my name. I painfully shared my new health story with my dissertation advisor who was shocked to see me completing the mundane activities associated with completing my dissertation. Shouldn’t I be on some exotic trip living life to the fullest? I smiled at that, and figured it was too soon to start hitting my bucket list. After all, I still had not received a definitive diagnosis of what the anomaly was in my brain scan. As it turned out, I was supposed to have a job interview for a research position at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia but needed to postpone that, along with another interview I was invited to at Maine Medical Center Research Institute. I didn't feel right having PI’s invest in interviewing me at this time when there were so many unanswered questions about my future.

My next step was going to the Mayo Clinic where I met with a neurologist and neurosurgeon to determine the course of action. We discussed my symptoms—difficulty focusing attention, a feeling that my eyes were not operating in synchrony any longer, dizziness and, likely due to the stress of now being a brain scientist with a brain tumor, panic attacks. After all the information was in, it was decided that surgery was imminent. Without looking at anyone else in the room, I said, “well I am penciled into your schedule for Monday (It was Wednesday), how does that sound?” The surgeon looked at me with a smile and said, “Sounds good.” At this point, I realized my neuroscience education was coming full circle whether I wanted it to or not. The many brain surgeries I had done on rats in graduate school took on a new meaning as I contemplated being on the receiving side of the brain surgery equation.

Thankfully, the surgery was thought to have gone well. The neurosurgeon reported that thought he had removed pretty damn close to all of the tumor. He also confirmed that surgery was the right decision in this bizarre brain journey. At that point, the tumor was sent off for pathology and we should have the report by the end of the week. After leaving the hospital I didn’t give much thought to the pathology report because both neurosurgeons believed it was most likely benign. So I should be able to get back to normal life as soon as I recovered from surgery. But there were additional surprises in this story. When the pathology results were read, I don’t think I truly processed what I was hearing. I had an anaplastic astrocytoma, part grade 2 but also part grade 3 (cancer). I hadn't done a ton of research on types of gliomas, but I knew enough that astrocytoma was something I didn’t expect to hear. This was another barrier to getting on with my future; once again, my life had to be put on hold. A course of action to treat the tumor was decided upon including 6 weeks of radiation combined with chemotherapy --followed by a another year of chemotherapy.

As I moved into the Hope Lodge (run by the American Cancer Society) for the duration of treatment, I decided that I wanted answers to the difficult questions regarding my tumor, which I had been avoiding. In my mind, I needed to prepare myself for whatever the answers were going to be. "There is no cure,” my doctor told me. “No matter what we do, the tumor is going to come back." So, that was a blow, yet one more “prediction error” that my neural networks was forced to process. I don't think I had even really given much thought to the fact that I was going to have to live with this for the rest of my life. More details were revealed, the tumor tissue showed increased mitosis indicating that the cells were considered somewhat aggressive. Surgery had removed most if not all of those cells and it was hoped that radiation and chemo would kill anything that may have been left behind. I was told that, when the tumor did return, it would be about a cm or 2 from where the original tumor was located. I then asked about all the requisite probabilities of future tumor-related events. I learned that the longest my doctor had seen a patient go without a recurrence was 6 years. Okay -- that was a fairly long time and recurrence just means that we have to figure out how to get rid of the tumor again. The question running through my head was why the hell am I going through all of this if the dang tumor is coming back anyway. I was also reminded that, even though the tumor was categorized as a grade 3, some of the tumor was grade 2, so that was encouraging. My mind was racing because in all honesty, as a neuroscientist, I knew too much. Even though I had come through my initial surgery with minimal long-term effects, I knew what would happen if the tumor came back. It would destroy brain tissue in the temporal lobe area that I needed for important functions---vision, emotional processing, memories----so easily taken for granted just a short time ago I have worked so hard to achieve my goals of teaching and conducting research, the thought of losing my ability to be a professor and scientist were crushing.

Fast forward three years. After full recovery, the only signs I of surgery are a long scar along the right side of my head, a small wedge shaped loss of vision in my left eye (the geniculate nucleus was nicked during surgery) and some changes to memory. I remain in remission and see the neuro-oncologist 3 times a year at which time I have an MRI to check for regrowth. I’m well aware of how valuable my existing brain real-estate is so it is imperative that we catch the tumor in its earliest stages should it reappear. I am completing a postdoctoral fellowship at a small liberal arts college, Randolph-Macon College, where I have had the opportunity to supervise undergraduate research projects on various projects exploring environmental-based neuroplasticity in collaboration with Kelly Lambert. I have also taught several courses including Brain and Gender, Research Methods, and Behavioral Neuroscience. I look forward to continuing working with students in a similar position in the Lambert lab at the University of Richmond, after which, I look forward to securing a tenure-track position and starting my own lab. Students convey that my personal story motivates them to want to learn more about the brain. We all follow the research related to tumor growth very closely. In an unexpected way, neuroscience research has become very personal. At my most recent appointment, I was informed that my prognosis for regrowth has changed from 6 years to 15 years. Nothing is guaranteed, but that was welcomed news. I’m betting on the science these days, hoping new treatments will emerge. When or if the tumor returns, I will continue to fight, I will continue to dream, and I will continue to be me.

In the Field with Dr. Stan B. Floresco

by Rastafa I. Geddes

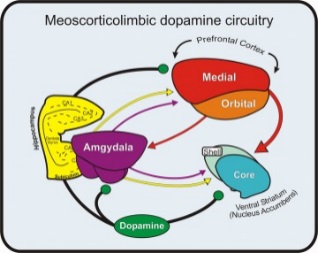

Research Summary: The Floresco lab research focuses on neural circuits that facilitate different forms of learning/cognition using rodents as a model system. We are particularly interested in the interactions between different brain regions within the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system that facilitate cognitive processes. Our laboratory uses a multidisciplinary approach, combining behavioral & psychopharmacological assays, along with neurophysiological recordings in both anesthetized and awake rodents. Research Summary: The Floresco lab research focuses on neural circuits that facilitate different forms of learning/cognition using rodents as a model system. We are particularly interested in the interactions between different brain regions within the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system that facilitate cognitive processes. Our laboratory uses a multidisciplinary approach, combining behavioral & psychopharmacological assays, along with neurophysiological recordings in both anesthetized and awake rodents.

Recent Publications:

Stopper CM, Tse MT, Montes DR, Wiedman CR, Floresco SB. Overriding phasic dopamine signals redirects action selection during risk/reward decision making. Neuron. 2014;84:177-89.

Dalton GL, Wang NY, Phillips AG, Floresco SB. Multifaceted Contributions by Different Regions of the Orbitofrontal and Medial Prefrontal Cortex to Probabilistic Reversal Learning. J Neurosci. 2016; 36:1996-2006.

Expert Advice for Before IBNS 2017: Prioritize posters you want to see; try to allocate more time for ones that are directly related to your work (as you may run out of time in the session). Read up on recent papers related to the work you’re presenting so that you can integrate your findings with the broader literature.

During IBNS 2017: Write down references to data presented in talks. Don’t be shy to approach more senior investigators to discuss the work- you may be surprised how enjoyable the experience will be (for both of you). Make use of the socials, not just to have fun, but to get to know peers in your field- many of these early relationships you form at this stage of your training can last throughout your career. Be sure to enjoy the city you’re in. And try to get some sleep (particularly the night before you present).

After IBNS 2017: Exchange notes with your lab mates- they may have seen data that you missed, but would be of interest to you (and vice versa). Feed of the motivation you got from this meeting to collect data you’ll present at the next one. Oh, and catch up on some sleep.

Dr. Jaak Panksepp - A mind of joy and research

Dr. Jaak Panksepp, whose ground-breaking research into the neuroscience of emotions lowered the barrier between humans and other species with who we share this planet, passed away on April 18th of this year at his home in Bowling Green, Ohio. Dr. Pankseep learned in November that he was suffering squamous cell carcinoma but continued his research, even going to campus on crutches through late February (http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/toledoblade/obituary.aspx?n=jaak-panksepp&pid=185145174&fhid=3252). At the time of his death, Dr. Pankseep was Emeritus Professor of Psychology at Bowling Green State University and Professor and Bernice Gilman Baily and Joseph Baily in Animal Well-Being Science in the College of Veterinary Medicine at Washington State University. Dr. Panksepp is the author and co-author of many publications, including Affective Neuroscience: The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions (2012), Textbook of Biological Psychiatry (2003), and The Archaeology of Mind: Neuroevolutionary Origins of Human Emotions (2012) with Lucy Biven and Evolution, Early Experience and Human Development: From Research to Practice and Policy (2012) with Darcia Narvaez.

In 2005, Dr. Panksepp commented on the origins of human laughter and joy and found those antecedents in other species - rats, dogs and chimps (Science 308, 62 (2005)) Indeed, his famous observation that rats, when tickled generate 50 kHz chirps which appear analogous to human laughter (J. Panksepp and J. Burgdorf (2003) Physiology and Behavior 79, 53; J. Panksepp (1998). Affective Neuroscience (Oxford Univ. Press: New York), opened up new possibilities for the treatment of depression and other mental conditions while firmly aligning humanity within the evolutionary continuum of Earth's species. In a 2012 interview with Discovery magazine, Dr. Panksepp recounted his role as he 'rat tickler' along with his research charting the 7 networks of emotion: seeking; rage; fear; lust; care; panic/grief and play (http://discovermagazine.com/2012/may/11-jaak-panksepp-rat-tickler-found-humans-7-primal-emotions). His observations are also available in his delightful 2014 TED talk, The Science of Emotions (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=65e2qScV_K8).

Dr. Panksepp is well-known to the Society's membership, having delivered been a keynote speaker for the 2015 Annual Meeting in Victoria British Columbia. His passion, humor and wide-ranging and curious mind will be sourly missed. Perhaps, however, Dr. Panksepp himself put it best when he quoted William Blake (Auguries of Innocence (1863)) in that 2005 article in Science:

It is right it should be so;

Man was made for joy and woe;

And, when this we rightly know

Through the world we safely go.

Joy and woe are woven fine

A clothing for the soul divine;

Under every grief and pine

Runs a joy with silken twine.

It is our joy - and the global community's - that we were blessed with Dr. Panksepp's search for the biology of happiness and emotion.

Dr. Panksepp is survived by his wife, Anesa Miller; son, Jules Panksepp; stepdaughters Antonia Pogacar and Ruth Pogacar-Kouril, and a step-granddaughter.

IBNS 2017 in Hiroshima, Japan

Join the IBNS for the 26th Annual Meeting on June 26-30, 2017, in Hiroshima, Japan, where you will listen to leaders in the field of behavioral neuroscience, have the opportunity expand your professional network with renowned scientists and researchers from all over the world, and showcase your own scientific contributions, while visiting a culturally rich society of the eastern hemisphere. Join the IBNS for the 26th Annual Meeting on June 26-30, 2017, in Hiroshima, Japan, where you will listen to leaders in the field of behavioral neuroscience, have the opportunity expand your professional network with renowned scientists and researchers from all over the world, and showcase your own scientific contributions, while visiting a culturally rich society of the eastern hemisphere.

There is still time to register and attend this excellent conference. Find out more... http://www.ibnsconnect.org/ibns-2017-annual-meeting

Hobby Much?

Wondering who the kayaking hobbiest is from the last edition of IBNS News? It was our very own Kimberly Gereke, currently at Rhodes College in Memphis, Tennessee.

Trending Science

In this column, we will share the latest research, interesting scientific articles and news you can use.

Researchers at Northwestern University discover that emotional behavior may depend critically on whether you are inhaling or exhaling and whether you are breathing through your nose or through your mouth. Read more HERE.

Member News

We congratulate Dr. Davide Amato, recently appointed Research Assistant Professor at the Department of Neuroscience of the Medical University of South Carolina. We congratulate Dr. Davide Amato, recently appointed Research Assistant Professor at the Department of Neuroscience of the Medical University of South Carolina.

Davide will be working on the cortico-striatal thalamo-cortical loop in the context of addiction, psychosis and their treatment.

Do you have an interesting hobby or member news to share?

Let us know at [email protected]

|