|

In This Issue...

- Social Drinking

- Hobby Much?

- Meet the IBNS Career Center

- Trending Science

- 2018 Annual Meeting Venue

Social Drinking

by Cindy Barha, Guest Editor

We know that alcohol consumption has important health-related consequences. However, despite this knowledge, many of us still consume alcohol in varying amounts, especially in social settings. So why do humans engage in social consumption of alcohol? We posed this question, along with several others, to five world renowned IBNS members with expertise in alcohol and addiction research.

George Koob George Koob

Director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

Aaron White, Senior Office of the Director NIAAA Advisor

Why do you think people drink in a social context?

There are both positive and negative reinforcement mechanisms involved that lead people to drink in social contexts. Many people drink in social contexts because alcohol is a "social lubricant." As outlined in the alcohol chapter in Koob and Le Moal (Neurobiology of Addictionm, 2006, Elsevier), alcohol facilitates social interactions by reducing social inhibitions and increasing the chances that people will talk to each other. Many people find social interactions pleasurable, providing positive reinforcement for drinking in a social situation. Others find social situations highly aversive and even terrifying and here alcohol's anti-anxiety effects provide negative reinforcement, or drinking to relieve a negative emotional states, by making the interactions less uncomfortable. Both types of reinforcement increase the chances that a person will choose to drink in a social context again. So, there are powerful, motivating factors that support drinking in a social context. Expectations also play a role. If a person learns to associate drinking with socializing, they might drink in social contexts simply because they think it's normal.

In your opinion, what is the impact of social consumption, non-addictive use, of alcohol on mental health in the short and long term?

You define social drinking here as non-addictive use but that is not always the case. Drinking responsibly can be defined, from a social standpoint, as drinking in a way that minimizes the risk of harm to oneself and others. It is entirely possible that a person who engages in responsible social drinking while in social contexts could actually have an alcohol use disorder, AUD. Please see our website, Rethinking Drinking, for the specific criteria used to define mild, moderate, and severe AUD [https://www.rethinkingdrinking.niaaa.nih.gov/].

NIAAA has guidelines for drinking in a way that carries a low-risk of AUD: up to seven drinks per week for women, no more than three on a given day; and up to 14 drinks per week for men, no more than four on a given day. At these levels, only about two out of 100 people will meet criteria for DSM-IV or -5 AUD. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, or HHS, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, USDA, have dietary guidelines for general health effects of alcohol: no more than one drink per day for women, two drinks per day for men.

There are few untoward effects of alcohol consumption if one follows the guidelines above. In fact, evidence suggests that drinking at these low levels could prolong life for some people. However, there are serious untoward negative effects of binge drinking (four or more drinks for a woman or five or more drinks for a man over a two hour period), heavy drinking (binge drinking five or more times per month) and extreme binge drinking (drinking at levels two or more times the binge threshold in one session, so eight or more drinks for a woman or ten or more for a man). More than half of the deaths caused by alcohol each year, approximately 50,000 out of 90,000, are caused by acute, alcohol misuse, such as getting drunk at a party, rather than chronic alcohol use.

Alcohol misuse often follows the development of mental health conditions, like depression and anxiety disorders, but can also contribute to them. Feelings of anxiety and depression can increase greatly the day after even a single night of overindulgence. With chronic drinking, tolerance develops to the anxiety reducing effects of alcohol, prompting higher levels of consumption to achieve the desired negative reinforcement. Over time, the drinker can become stuck in a cycle of binge/intoxication, withdrawal/negative affect, and preoccupation/anticipation known as the “dark side” of addiction. A person might start drinking primarily for the positive reinforcement it provides. Yet, over time, they could find themselves drinking more and more for the negative reinforcement, to keep uncomfortable withdrawal symptoms at bay.

Are there sex and/or gender differences at play in this? Why or why not?

Yes. Females have less water per kilogram of body weight than males, so there is less fluid available to dilute the alcohol. As a result, a female will reach a higher blood alcohol level after each drink than a male of the same weight, potentially leading to greater impairments in cognitive functions, like impulse control and decision-making. Perhaps partly because of differences in body water, females are more likely than males to experience alcohol-induced amnesia, or blackouts. Over time, females are more likely than males to develop breast cancer, the risk of which increases even with one drink per day. Females also develop AUD, liver inflammation and brain damage more quickly than males.

Research suggests that females might be more likely than males to drink to cope with symptoms of mental health conditions, particularly anxiety disorders. Women with existing anxiety disorders are more likely to misuse alcohol and develop AUD than men with anxiety disorders, and women who develop AUD are more likely than men to have a comorbid anxiety disorder. The co-occurrence of an anxiety disorder complicates the treatment of AUD in part because anxiety levels can be heightened for weeks or months following cessation of drinking, providing strong motivation to return to use.

Are the relationships between social alcohol consumption and mental health similar across the lifespan?

There is little evidence of an increased risk of mental health or other health issues for adults who keep their alcohol use within low-risk/moderate limits. While AUD is more common in people with severe mental health issues, low levels of alcohol use do not appear to increase the risks.

Adolescence is a stage of development during which the likelihood of alcohol use, depression and anxiety all increase. There is strong evidence of associations between alcohol use and mood disorders and the influence appears to be bi-directional. Alcohol misuse often precedes the development of depression and anxiety disorders and worsens their prognoses. For other teens, mood disorders begin first and alcohol misuse follows in an effort to cope with symptoms. The prognosis for AUD and mood disorders are worse when they co-occur.

The population of adults aged 65+ is growing rapidly. An estimated 1 in 4 older adults has a mental disorder, mostly commonly depression, anxiety disorders or dementia. Levels of alcohol use and AUD have been increasing in this population, and alcohol produces bigger impairments in balance, coordination, and reaction times, and bigger increases in sedation, in older compared to younger drinkers. Further, many older adults take medications that could interact negatively with alcohol. These developments raise concerns about unintentional injuries as a result of alcohol and medication interactions in older drinkers, and complications in care for older adults with mental disorders who also drink excessively.

What role, if any, do you believe governmental bodies have in regulating social alcohol consumption? Can social drinking be considered a risk factor for addiction?

The legal drinking age is 21 in every state in the Union. The law was passed by all the United States during the Reagan administration and has contributed to a nearly 50% decrease in drunk driving fatalities over the past 30 years. All states also have zero tolerance laws for drinking and driving for people under 21, making it illegal for people under the legal drinking age to drive after even one drink.

For people aged 21 and older, the legal limit for drinking and driving is a BAC of 0.08%. This level is reached by most people after consuming 4 (women) or 5 (men) drinks in a two-hour period, roughly the equivalent of an entire bottle of wine during a two-hour dinner. Certainly, this is beyond what would be considered responsible social drinking.

Evidence suggests that the likelihood of harm is low if adults stay within low-risk or moderate drinking guidelines, including while socializing. The risks of injuries, health consequences and developing AUD are small, and alcohol might even benefit health at these levels. In contrast, drinking beyond low-risk or moderate levels costs the United States approximately 90,000 lives and $250 billion dollars annually. NIAAA does not participate in the regulation of alcohol or make recommendations for doing so. We provide evidence based information about the health effects of alcohol that allows citizens to decide on appropriate alcohol regulations at the local, regional, state and federal levels.

Christian P. Müller Christian P. Müller

Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy

University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany

Why do you think people drink in a social context?

Alcohol is a widely used psychoactive drug in western societies. Although it is generally acknowledged as a pharmacological reinforcer, those properties cannot explain the rather situation specific use of the drug, as it applies in particular for social situations. Although alcohol may enhance the reinforcing value of social interaction, it has far more effects than that. We believe that alcohol can be instrumentalized to enhance an individual’s performance in those situations. Alcohol has in low-medium doses pharmacological effects that support a mental state which is beneficial for social interactions. It allows a stressed individual, e.g. at the end of a long working day, to better relax, disinhibit approach behavior and temporarily loose some of its innate and conditioned anxieties. By that way, alcohol can be an effective behavioral support in a social context, which may explain its widespread but yet selective use.

In your opinion, what is the impact of social consumption, non-addictive use, of alcohol on mental health in the short and long term?

There are now numerous, well-controlled studies that show a better mental and physical health in people who regularly consume a small amount of alcohol compared to complete abstainers. However, alcohol at higher doses is still a toxin. Even when consumed in a social context with successful instrumentalization for more effective socializing, it may when consumed too frequently or in too high amounts have adverse health effects in the long run.

Are there sex and/or gender differences at play in this? Why or why not?

There are strong gender effects in alcohol consumption and the risk to develop alcohol addiction. However, potential benefits of social drinking in specific contexts, like a bar or restaurant, are used by both genders. Who is more efficient in that, remains an open question.

Are the relationships between social alcohol consumption and mental health similar across the lifespan?

Alcohol is consumed for different reasons across the lifespan. At young adulthood the social context is often the peer group and a major goal is the search and approach of a future partner. Later in life, when family and job is secured, coping with stress – even the stress of job success – in a social context may become more important. As such, social drinking may serve quite different functions and yield different benefits at different ages. However, it also holds the risk for age-specific trajectories into addiction.

What role, if any, do you believe governmental bodies have in regulating social alcohol consumption? Can social drinking be considered a risk factor for addiction?

Any type of alcohol drinking is, per se, a risk factor for addiction. Also social drinking, in particular when the alcohol effects are successfully instrumentalized. However, this is an accepted behavior in western societies, which is to some extent controlled and limited by the social group. In that, beer and wine social drinking is part of our cultural identity. Governmental bodies may not be needed to strictly control it. However, health policy should increase awareness in the consumers of the potential danger of the drug itself and the risks that arise from drug over-instrumentalization.

Peter W. Kalivas Peter W. Kalivas

Professor, Department of Neuroscience

Medical University of South Carolina, USA

Why do you think people drink in a social context?

I think social drinking serves two important purposes. First, it’s a form for self-medication of social anxiety. The other reason is the social bonding that occurs in shared activities liking laughing and relaxing with friends. Alcohol is such a poor releaser of dopamine, it seems to me that alcohol use at least initially may require a parallel, associated rewarding activity to develop into a reinforcer on its own, i.e. activities such as socializing, high sugar content in pina coladas, etc.

In your opinion, what is the impact of social consumption (non-addictive use) of alcohol on mental health in the short and long term?

For the majority of people, the impact of low dose short term use is largely positive. Decreased anxiety and social bonding are generally good. High dose long-term use in social settings of course leads to all sorts of potential problems, from excessive social disinhibition to addiction. This is a greater problem in adolescents for biological and sociological reasons, and should be regulated to minimize excessive consumption through existing regulations on age of purchase and use, as well as enforcement in particularly prone situations, like fraternities.

Are there sex and/or gender differences at play in this? Why or why not?

My own sense is that sociological sex differences play a greater role than biological sex differences in most cases. Look at the fundamentals, social drinking occurs in both sexes for pretty much the same reasons and with the same generally positive outcomes with social use and negative outcomes with excessive use. Although the drug pharmacology is largely similar, this does not mitigate the need to target individual therapies in a way that include sociological sex-based differences, but this is true for any form of behavioral therapy.

Are the relationships between social alcohol consumption and mental health similar across the lifespan?

There is clear comorbidity between many psychiatric disorders and alcohol use disorder. But if you stay in the context of purely social use, my sense is that it could lower the threshold for manifesting maladaptive behaviours, such as depression and PTSD, but in the majority of people it is neutral or beneficial to mental health. However, I believe the data are clear, both biological and sociological, that adolescence is a vulnerable period in the lifespan for developing maladaptive alcohol use behaviors that create a greater likelihood for developing comorbidity with psychiatric disorders. The vulnerability of adolescents is in part a result of the developmental nature of many psychiatric disorders, which constitutes an epigenetic vulnerability that I believe can be exacerbated by psychoactive drugs, including alcohol.

What role, if any, do you believe governmental bodies have in regulating social alcohol consumption? Can social drinking be considered a risk factor for addiction?

Of course social use is a risk factor for addiction, like oxygen is a risk factor for oxidative stress. However, many centuries of social alcohol use have proven that the proportion of social users becoming addicts is relatively low (~10%) compared to more addictive drugs like cocaine and heroin, and this is apparently tolerable within the structure of most societies; although the extent of damage varies across cultures. Drug availability increases addiction. This is clear from the number of addicts to legal drugs like alcohol and nicotine versus many illegal drugs that are often much more addictive in a pharmacological sense but less available. In sum, my own sense is that government should strongly regulate maladaptive behavior associated with high dose alcohol use, such as drunk driving, hazing, etc., but should have little role in regulating social use of the drug beyond current laws controlling sites, hours and age of public use.

J. Leigh Leasure J. Leigh Leasure

Associate Professor, Department of Psychology

University of Houston, USA

Why do you think people drink in a social context?

There is a large literature in the social psychology field on drinking motives. One such motive is to facilitate social interaction. Alcohol quells anxiety, including social anxiety. It may also be a prominent aspect of the social context, for example, a meal or a celebration. People also drink in a social context because that social context is specifically geared to the consumption of that beverage among like-minded participants. For example, many people like the taste of wine and enjoy sampling wines with other people who enjoy it. The same is true of people who like craft beers or artisan cocktails.

In your opinion, what is the impact of social consumption, non-addictive use, of alcohol on mental health in the short and long term?

“Social drinking” means that the drinking in question is accepted by the society in which it is occurring, and that means “society” on the micro level; or in other words, the people that you are with. So, if that social drinking means you are having one drink a day, total, in the presence of others, I see only positive benefits for mental health. Notably, I think it is the social interaction providing the benefits. If, on the other hand, the social context involves binge drinking, I think that negatively impacts mental health. Binge drinking is defined by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism as a pattern of intake that brings the blood alcohol content to 0.08% (approximately 4 drinks for women/ 5 for men in 2 hours). Research in humans and in animal models indicates that this type of drinking pattern damages the brain and cognition.

Are there sex and/or gender differences at play in this? Why or why not?

There are well-established sex differences in the negative effects of alcohol. Women are more vulnerable to everything from alcohol-related accidents to alcohol-induced heart and liver damage. Some human neuroimaging studies even indicate that women’s brains are more vulnerable to alcohol than men’s, and results from animal studies uphold the idea that the female brain is selectively vulnerable to alcohol damage.

Are the relationships between social alcohol consumption and mental health similar across the lifespan?

Probably, assuming that the reasons people drink socially early in life are the same reasons that they drink socially later in life.

What role, if any, do you believe governmental bodies have in regulating social alcohol consumption?

I believe the role of government agencies is to make health recommendations regarding alcohol intake, based on research findings. I believe it is their role to provide concrete recommendations based on empirical data, and to make those guidelines clear, and easy to access and understand. Below is an NIAAA site on “What Is a Standard Drink?” I particularly like this site because I think most people do not realize that one drink is not necessarily one serving of alcohol.

[https://www.rethinkingdrinking.niaaa.nih.gov/How-much-is-too-much/What-counts-as-a-drink/Whats-A-Standard-Drink.aspx]

Can social drinking be considered a risk factor for addiction?

I’m going to treat this as a separate question, but refer to the definition of social drinking in my previous answer with #2. If the social drinking you are engaging in is binge drinking, then absolutely, that is very risky drinking. If the social drinking that you are doing is a maximum of one drink a day, then that is much less risky. But the only way to avoid an alcohol use disorder is not to drink alcohol.

Robert Gerlai Robert Gerlai

Professor, Department of Psychology

University of Toronto, Canada

Why do you think people drink in a social context?

Alcohol is a highly complex drug from the perspective of the many neurobiological processes it alters. Due to the large number of neurobiological mechanisms affected by alcohol, the behavioral effect profile of this substance is also quite complicated. Briefly, when you drink alcohol you feel the effect in many different ways. One of this feelings is euphoria, the other, perhaps related, is reduced anxiety. Yet other effects are reduced ability to evaluate complex social and other signals. Many of these effects may make the consumer of alcohol feel less inhibited in a social situation. Social interaction, albeit is a fundamentally species specific characteristic of our species, comes with a lot of negative aspects. Most people experience at least some degree of fear or anxiety when meeting new people when in front of a crowd. Evaluation of social cues is a time consuming and complex process that is often intimidating, even for those who do not admit it. The anxiolytic effects of alcohol may “help” one to overcome this fear. Similarly, alcohol’s effects on our ability to evaluate and understand complex social cues may also, paradoxically, make one feel more emboldened in a social context because the person is not receiving/perceiving potentially negative social cues. The ability of alcohol to hitch-hike the dopaminergic reward pathways (euphoria) may also contribute to social drinking.

In your opinion, what is the impact of social consumption (non-addictive use) of alcohol on mental health in the short and long term?

Alcohol consumption is engrained in most human societies across the Globe. We see movies, we read books, we listen to music and in all we find constant references to alcohol drinking being acceptable and in fact often viewed as being great. Also, alcohol is a legal drug. For these reasons, most assume it is safe. But just like most other drugs, alcohol does alter brain chemistry and many aspects of our neurobiology. It is an addictive substance that when consumed in large amount (binge drinking) acutely, or when consumed over a prolonged period of time (chromic exposure) or when consumed by pregnant women (embryonic alcohol exposure) does have negative health consequences. Some of these relate to mental health. Depending on someone’s genetic predispositions as well as his/her environment, alcohol can be a highly addictive and dangerous substance. I would also point out, that “social consumption” of alcohol is not a synonym of non-addictive use of alcohol. Again, depending on one’s genetic predisposition, social drinking can lead to alcohol dependency, alcohol abuse, and significant negative health consequences. How much is acceptable, and where we need to draw the line, are highly complicated scientific as well as personal questions. But the common-place does apply here too: alcohol drinking in moderation likely is OK.

Are there sex and/or gender differences at play in this? Why or why not?

The literature on sex differences in alcohol drinking, the type of alcohol consumption, the effect of alcohol consumption on health and mental health is huge. I won’t be able to reiterate the findings here. Instead, I would also mention the large sex differences in social behavior in humans and the possible interaction between such differences and the sex-dependent effects of alcohol. Briefly, there are many sex-specific differences in this context.

Are the relationships between social alcohol consumption and mental health similar across the lifespan?

Yes. Particularly interesting, from a scientific perspective, is the difference between the period of adolescence and adulthood in this context.

What role, if any, do you believe governmental bodies have in regulating social alcohol consumption? Can social drinking be considered a risk factor for addiction?

Definitely. Any type of drinking, whether it is in a social context, or at home alone, can be a risk factor for alcohol addiction. I believe education is the best way Government can help. I think honest and reasonable discussion about what the dangers are, and why people drink alcohol is a way to go.

Hobby Much?

by Rachel Navarra

As research scientists, most of us understand the never-ending battles against seemingly impossible deadlines, the frustrations of failed experiments, and criticism or flat out rejection of our most cherished work. Even when things are going well, we put so much of ourselves into our work that it is all too easy to forget to look out for our well-being outside of the laboratory. Practicing yoga has become one of my favorite activities for maintaining a balanced lifestyle.

My first introduction to yoga was during graduate school at Drexel University College of Medicine. It was during one of those particularly tedious waves when nothing was working and everything seemed stacked against me. Although I knew that things would ultimately work out, either by means of persistent trouble shooting or a switch in strategy, it occurred to me that I was so consumed by the drama of the day-to-day rigors of research, that I didn’t have much else to serve as a positive distraction. When I tried to think of an activity or hobby I enjoyed outside of work, I realized I didn’t really have anything to help me unwind and combat the “burn out” that didn’t involve grabbing drinks here and there with friends. On a graduate student stipend, there aren’t a tremendous amount of activity options to explore, especially when it’s cold in Philly. Yoga was one of the free classes that Drexel’s Wellness Program offered and I decided to give it a try. Yoga can be super awkward at first! There are a dizzying array of new words, commands, and poses, or asanas, to learn. You look around and there are some so experienced in their practice that they can literally twist themselves into a human pretzel while balancing all of their body weight on a single hand! It is easy to feel like the most uncoordinated person in the world and judge yourself compared to others, but sticking with it and learning to accept yourself for where you are in your own practice is definitely worth it!

Over the years, my yoga practice has taken on two different forms. I can’t say which is more important, because both of them make me happy and lift my spirits in different ways. There’s a private component: one that I only share with those I practice with and myself. Then there’s another component: one where I like to participate via social media with friends and others who practice yoga.

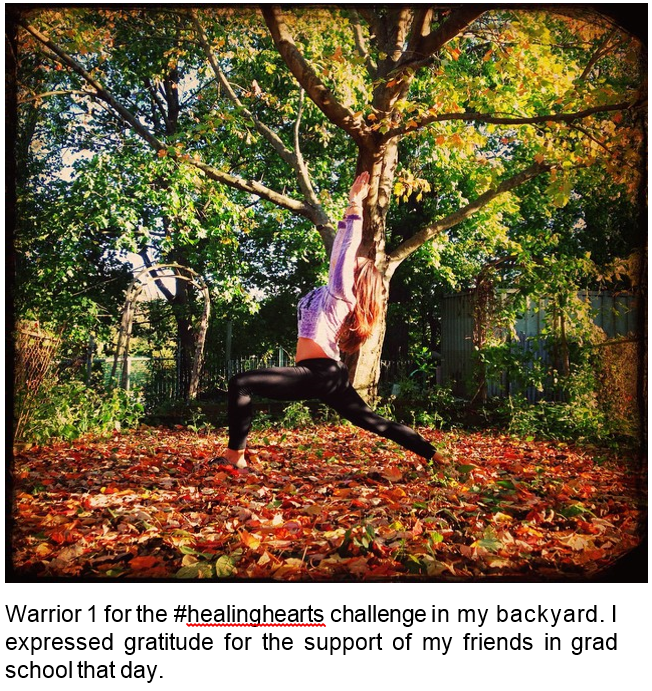

In November 2014, I tried my first Instagram yoga challenge. It was called #HealingHearts and was hosted by @kinoyoga and @beachyogagirl. The challenge focused on gratitude and heart opening postures for the month leading up to Thanksgiving. Basically, each day you post a picture of yourself in a heart opening asana and briefly express or write about something you are grateful for. I wanted to give it a shot, so at the expense of feeling self-conscious, I did. It was a lot of fun! And it was really challenging! Figuring out how to make some of these bizarre but amazing shapes with my body, exploring my strength and flexibility, learning how I can develop my strength and flexibility, so many new things! I learned so much about myself, both in terms of my limitations and also new breakthroughs I didn’t think were possible before. I made it a point every day that month to consciously focus my energy towards acknowledging and appreciating the things in my world for which I am grateful. So many brilliant feelings, both body and mind! I was hooked. In November 2014, I tried my first Instagram yoga challenge. It was called #HealingHearts and was hosted by @kinoyoga and @beachyogagirl. The challenge focused on gratitude and heart opening postures for the month leading up to Thanksgiving. Basically, each day you post a picture of yourself in a heart opening asana and briefly express or write about something you are grateful for. I wanted to give it a shot, so at the expense of feeling self-conscious, I did. It was a lot of fun! And it was really challenging! Figuring out how to make some of these bizarre but amazing shapes with my body, exploring my strength and flexibility, learning how I can develop my strength and flexibility, so many new things! I learned so much about myself, both in terms of my limitations and also new breakthroughs I didn’t think were possible before. I made it a point every day that month to consciously focus my energy towards acknowledging and appreciating the things in my world for which I am grateful. So many brilliant feelings, both body and mind! I was hooked.

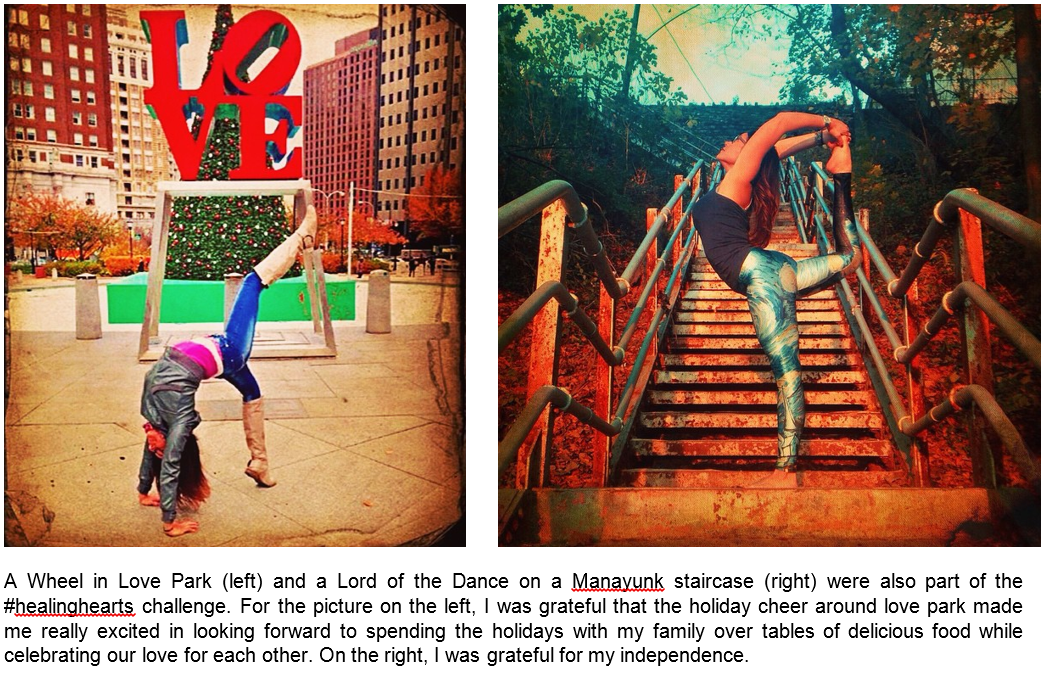

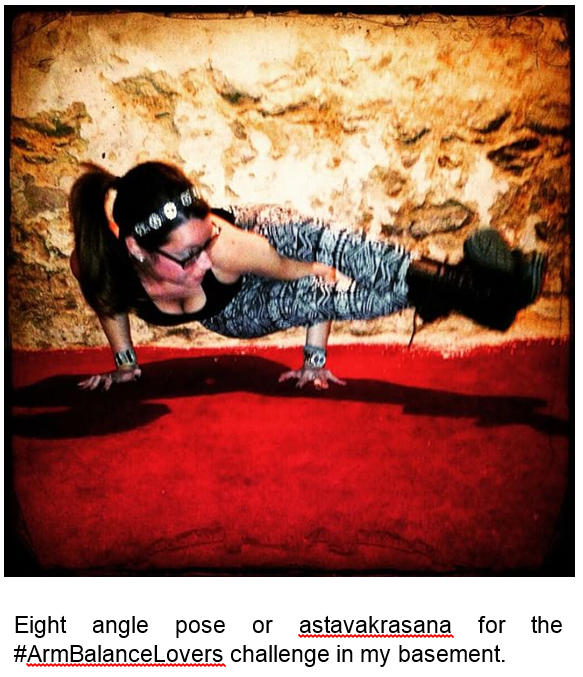

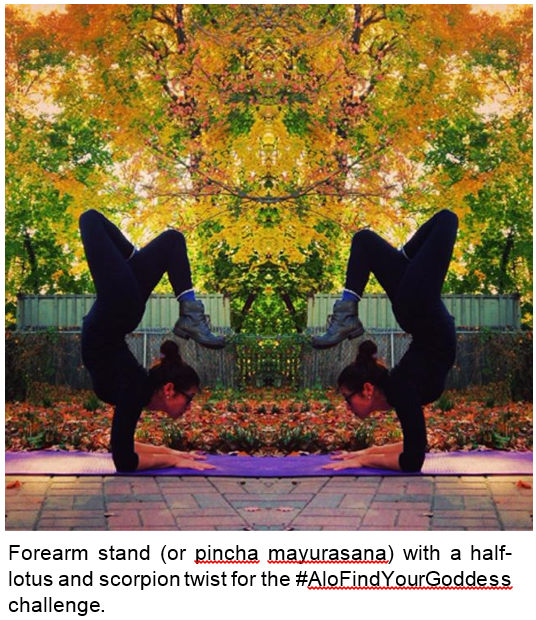

I’ve participated in handfuls of yoga challenges since the first #HealingHearts challenge, all with their own special twist. Some challenges focus on a deeper and more spiritual side, others are more on the playful and gimmicky side. I posted pictures that were taken from yoga studios, my house, the lab, around Philly, and while traveling. I included places and ideas that were special to me, or special to what I had going on at the time. I played with different camera angles, filters, and picture editing apps. It was a great way to explore my creativity. I was serious with it at times and silly at other times. I’ve participated in handfuls of yoga challenges since the first #HealingHearts challenge, all with their own special twist. Some challenges focus on a deeper and more spiritual side, others are more on the playful and gimmicky side. I posted pictures that were taken from yoga studios, my house, the lab, around Philly, and while traveling. I included places and ideas that were special to me, or special to what I had going on at the time. I played with different camera angles, filters, and picture editing apps. It was a great way to explore my creativity. I was serious with it at times and silly at other times.

These challenges have become such a great source of positive energy. They are a platform for both close friends and for the broader yoga community to support and cheer each other’s accomplishments. The challenges are about taking time for yourself among the hustle and  bustle of the everyday routine, allowing you to feel great about yourself (or learn where you need improvement), and encouraging you to express and share those great feelings (or momentary defeats). It has taken me months of relentless work to add some of these asanas to my practice. I’ve been practicing handstands for years and still haven’t been able to reliably catch more than a couple seconds of air-time. It takes a lot of courage to put yourself out there and share your journey with others, but I’ve always enjoyed myself along the way and felt pride with what I ended up creating. bustle of the everyday routine, allowing you to feel great about yourself (or learn where you need improvement), and encouraging you to express and share those great feelings (or momentary defeats). It has taken me months of relentless work to add some of these asanas to my practice. I’ve been practicing handstands for years and still haven’t been able to reliably catch more than a couple seconds of air-time. It takes a lot of courage to put yourself out there and share your journey with others, but I’ve always enjoyed myself along the way and felt pride with what I ended up creating.

Practicing yoga has challenged me to expand the ways I look for further growth and figure out how I can apply those developments to all aspects of my career and life. How can (or do) you use yoga or your favorite activity to help shine in different aspects of your career and life?

Looking for a new employment opportunity or struggling to find the right candidate? Meet the IBNS Career Center!

One of the biggest challenges for any international scientific society is to provide quality and informative support to its members, whether it is for a new employment opportunity or for finding the right candidate for a new position you opened. The IBNS excels in this area through its online Career Center portal (http://jobs.ibnsconnect.org) through which it provides the right tools for both, job seekers and employers.

The IBNS Career Center portal offers all the standard operational features, such as a thorough search engine by keyword and location, as well as extra services such as a free review of your resume for feedback and a job-posting service for employers. However, what makes the IBNS Career Center stand out in terms of support, is two additional quality features: resources for job seekers & access to a resume bank for employers.

In the Resources section you can have access to a number of articles with valuable tips in resume building, job seeking and communication, from experienced scientists in the field, not only for searching or applying for a position, but also for the interview process. There is also plenty of advice and tips for building your ‘brand’ and your social media presence, which will help you strengthen your image and moving your career to the direction you want.

In the Resume Bank, potential employers have free access to a large bank of resumes and profiles, which you can customize by introducing filters that apply to your search and create lists of candidates that fulfill your own criteria. In the Resume Bank, potential employers have free access to a large bank of resumes and profiles, which you can customize by introducing filters that apply to your search and create lists of candidates that fulfill your own criteria.

Trending Science

In this column, we share the latest research, interesting scientific articles and news.

by Cindy K. Barha, Ph.D, Postdoctoral Research Fellow

University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Why do women behave more prosocially than men?

Experimental studies have shown that females are more generous than males when sharing a sum of money. Soutschek and colleagues from the University of Zurich used both neuroimaging and pharmacological techniques to examine the neurobiological reason for this behavioral finding. They showed for the first time that female and male brains process prosocial and selfish behavior differently. Specifically, they found that the reward system was more strongly activated in female brains during prosocial decisions than during selfish decisions. On the other hand, in males stronger activation of the reward system was seen during selfish decisions. Furthermore, pharmacological disruption of dopamine led to more selfish behaviors in females and more prosocial behaviors in males. Although effects were small, this research suggests the neural reward system may be more sensitive to prosocial rewards in females than in males.

Alexander Soutschek, Christopher J. Burke, Anjali Raja Beharelle, Robert Schreiber, Susanna C. Weber, Iliana I. Karipidis, Jolien ten Velden, Bernd Weber, Helene Haker, Tobias Kalenscher, Philippe N. Tobler. The dopaminergic reward system underpins gender differences in social preferences. Nature Human Behaviour, 2017; DOI: 10.1038/s41562-017-0226-y

2018 Annual Meeting Venue Change

by F. Scott Hall, IBNS President

Change in venue for the 2018 annual meeting of the International Behavioral Neuroscience Society.

Shortly after Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico and other parts of the Caribbean, we at IBNS expressed our concern for our colleagues and the citizens of Puerto Rico, and encouraged our members to help where they could. We were determined to keep the meeting in Puerto Rico, if at all possible. We were initially assured by the hotel that they would be open within plenty of time for the meeting. Unfortunately, we were told last week that the repairs to the hotel would not be completed in time. The hotel will not open at all until April at the earliest, and will not be fully open for some time after that as portions remain closed for renovation on a rotating basis. As you are no doubt aware from news reports, the repairs to basic infrastructure in Puerto Rico are moving at an incredibly slow pace. Focus of all governmental and non-governmental groups remains on that basic infrastructure. As a consequence, relatively unimportant repairs (like the hotel) will be delayed while workers concentrate upon more important issues. This means that the hotel will not be able to host us next June. While we are disappointed in this outcome, we have accepted the circumstances. The representatives at El Conquistador have been very helpful in finding an alternative location, at relatively short notice. With their assistance we were able to maintain the same hotel pricing for the conference, including additional discounts for students. Thus, we wish to announce that the 2018 annual meeting location will be moved to the Boca Raton Resort and Club, Boca Raton, Florida (www.bocaresort.com). The dates will be almost exactly the same, June 27, 2018 to July 2, 2018.

Although we are all quite disappointed that we were unable to hold the meeting in Puerto Rico in June, 2018 as we had hoped, the IBNS Council will be discussing when we might be able to bring the meeting to Puerto Rico at a later date. That information will be forthcoming in the near future. The IBNS council will also be discussing ways that we might be able to help our Puerto Rican colleagues with meeting attendance, including registration waivers for our Puerto Rican colleagues and additional travel awards for Puerto Rican students (pending Council approval of course). Announcements about those efforts will be made after the Council meeting at the SFN Conference in November.

In the meantime, there continues to be an ongoing humanitarian crisis in Puerto Rico. We encourage all of our members to help where they can, and to contact their Senators and Representatives to encourage them to increase the commitment of federal resources to resolve this ongoing crisis. Additionally, we encourage our members to contribute where they can to the recovery effort. Information on how to help is available at FEMA, and volunteer resources of many organizations helping the recovery effort are coordinated through the National Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster.

F. Scott Hall, PhD, IBNS President

Carmen Maldonado-Vlaar, Chair of the Local Organizing Committee

Do you have an interesting hobby or member news to share?

Let us know at [email protected]

|